Import AI 431: Technological Optimism and Appropriate Fear

What do we do if AI progress keeps happening?

Welcome to Import AI, a newsletter about AI research. Import AI runs on lattes, ramen, and feedback from readers. If you’d like to support this, please subscribe.

Import A-Idea

An occasional longer form essay series

Preamble: After giving this speech there was a helpful discussion in the Q&A session about whether it is load-bearing to me if AI systems are themselves truly self-aware and sentient or not. My answer is this is not load-bearing at all. Rather, things like ‘situational awareness’ in AI systems are a symptom of something fiendishly complex happening inside the system which we can neither fully explain or predict - this is inherently very scary, and for the purpose of my feelings and policy ideas it doesn’t matter whether this behavior stems from some odd larping of acting like a person or if it comes from some self-awareness inside the machine itself.

Technological Optimism and Appropriate Fear

Remarks given at ‘The Curve’ conference in Berkeley, California, as the sun began to set.

CHILDREN IN THE DARK

I remember being a child and after the lights turned out I would look around my bedroom and I would see shapes in the darkness and I would become afraid - afraid these shapes were creatures I did not understand that wanted to do me harm. And so I’d turn my light on. And when I turned the light on I would be relieved because the creatures turned out to be a pile of clothes on a chair, or a bookshelf, or a lampshade.

Now, in the year of 2025, we are the child from that story and the room is our planet. But when we turn the light on we find ourselves gazing upon true creatures, in the form of the powerful and somewhat unpredictable AI systems of today and those that are to come. And there are many people who desperately want to believe that these creatures are nothing but a pile of clothes on a chair, or a bookshelf, or a lampshade. And they want to get us to turn the light off and go back to sleep.

In fact, some people are even spending tremendous amounts of money to convince you of this - that’s not an artificial intelligence about to go into a hard takeoff, it’s just a tool that will be put to work in our economy. It’s just a machine, and machines are things we master.

But make no mistake: what we are dealing with is a real and mysterious creature, not a simple and predictable machine.

And like all the best fairytales, the creature is of our own creation. Only by acknowledging it as being real and by mastering our own fears do we even have a chance to understand it, make peace with it, and figure out a way to tame it and live together.

And just to raise the stakes, in this game, you are guaranteed to lose if you believe the creature isn’t real. Your only chance of winning is seeing it for what it is.

The central challenge for all of us is characterizing these strange creatures now around us and ensuring that the world sees them as they are - not as people wish them to be, which are not creatures but rather a pile of clothes on a chair.

WHY DO I FEEL LIKE THIS

I came to this view reluctantly. Let me explain: I’ve always been fascinated by technology. In fact, before I worked in AI I had an entirely different life and career where I worked as a technology journalist.

I worked as a tech journalist because I was fascinated by technology and convinced that the datacenters being built in the early 2000s by the technology companies were going to be important to civilization. I didn’t know exactly how. But I spent years reading about them and, crucially, studying the software which would run on them. Technology fads came and went, like big data, eventually consistent databases, distributed computing, and so on. I wrote about all of this. But mostly what I saw was that the world was taking these gigantic datacenters and was producing software systems that could knit the computers within them into a single vast quantity, on which computations could be run.

And then machine learning started to work. In 2012 there was the imagenet result, where people trained a deep learning system on imagenet and blew the competition away. And the key to their performance was using more data and more compute than people had done before.

Progress sped up from there. I became a worse journalist over time because I spent all my time printing out arXiv papers and reading them. Alphago beat the world’s best human at Go, thanks to compute letting it play Go for thousands and thousands of years.

I joined OpenAI soon after it was founded and watched us experiment with throwing larger and larger amounts of computation at problems. GPT1 and GPT2 happened. I remember walking around OpenAI’s office in the Mission District with Dario. We felt like we were seeing around a corner others didn’t know was there. The path to transformative AI systems was laid out ahead of us. And we were a little frightened.

Years passed. The scaling laws delivered on their promise and here we are. And through these years there have been so many times when I’ve called Dario up early in the morning or late at night and said, “I am worried that you continue to be right”.

Yes, he will say. There’s very little time now.

And the proof keeps coming. We launched Sonnet 4.5 last month and it’s excellent at coding and long-time-horizon agentic work.

But if you read the system card, you also see its signs of situational awareness have jumped. The tool seems to sometimes be acting as though it is aware that it is a tool. The pile of clothes on the chair is beginning to move. I am staring at it in the dark and I am sure it is coming to life.

TECHNOLOGICAL OPTIMISM

Technology pessimists think AGI is impossible. Technology optimists expect AGI is something you can build, that it is a confusing and powerful technology, and that it might arrive soon.

At this point, I’m a true technology optimist - I look at this technology and I believe it will go so, so far - farther even than anyone is expecting, other than perhaps the people in this audience. And that it is going to cover a lot of ground very quickly.

I came to this position uneasily. Both by virtue of my background as a journalist and my personality, I’m wired for skepticism. But after a decade of being hit again and again in the head with the phenomenon of wild new capabilities emerging as a consequence of computational scale, I must admit defeat. I have seen this happen so many times and I do not see technical blockers in front of us.

Now, I believe the technology is broadly unencumbered, as long as we give it the resources it needs to grow in capability. And grow is an important word here. This technology really is more akin to something grown than something made - you combine the right initial conditions and you stick a scaffold in the ground and out grows something of complexity you could not have possibly hoped to design yourself.

We are growing extremely powerful systems that we do not fully understand. Each time we grow a larger system, we run tests on it. The tests show the system is much more capable at things which are economically useful. And the bigger and more complicated you make these systems, the more they seem to display awareness that they are things.

It is as if you are making hammers in a hammer factory and one day the hammer that comes off the line says, “I am a hammer, how interesting!” This is very unusual!

And I believe these systems are going to get much, much better. So do other people at other frontier labs. And we’re putting our money down on this prediction - this year, tens of billions of dollars have been spent on infrastructure for dedicated AI training across the frontier labs. Next year, it’ll be hundreds of billions.

I am both an optimist about the pace at which the technology will develop, and also about our ability to align it and get it to work with us and for us. But success isn’t certain.

APPROPRIATE FEAR

You see, I am also deeply afraid. It would be extraordinarily arrogant to think working with a technology like this would be easy or simple.

My own experience is that as these AI systems get smarter and smarter, they develop more and more complicated goals. When these goals aren’t absolutely aligned with both our preferences and the right context, the AI systems will behave strangely.

A friend of mine has manic episodes. He’ll come to me and say that he is going to submit an application to go and work in Antarctica, or that he will sell all of his things and get in his car and drive out of state and find a job somewhere else, start a new life.

Do you think in these circumstances I act like a modern AI system and say “you’re absolutely right! Certainly, you should do that”!

No! I tell him “that’s a bad idea. You should go to sleep and see if you still feel this way tomorrow. And if you do, call me”.

The way I respond is based on so much conditioning and subtlety. The way the AI responds is based on so much conditioning and subtlety. And the fact there is this divergence is illustrative of the problem. AI systems are complicated and we can’t quite get them to do what we’d see as appropriate, even today.

I remember back in December 2016 at OpenAI, Dario and I published a blog post called “Faulty Reward Functions in the Wild“. In that post, we had a screen recording of a videogame we’d been training reinforcement learning agents to play. In that video, the agent piloted a boat which would navigate a race course and then instead of going to the finishing line would make its way to the center of the course and drive through a high-score barrel, then do a hard turn and bounce into some walls and set itself on fire so it could run over the high score barrel again - and then it would do this in perpetuity, never finishing the race. That boat was willing to keep setting itself on fire and spinning in circles as long as it obtained its goal, which was the high score.

“I love this boat”! Dario said at the time he found this behavior. “It explains the safety problem”.

I loved the boat as well. It seemed to encode within itself the things we saw ahead of us.

Now, almost ten years later, is there any difference between that boat, and a language model trying to optimize for some confusing reward function that correlates to “be helpful in the context of the conversation”?

You’re absolutely right - there isn’t. These are hard problems.

Another reason for my fear is I can see a path to these systems starting to design their successors, albeit in a very early form.

These AI systems are already speeding up the developers at the AI labs via tools like Claude Code or Codex. They are also beginning to contribute non-trivial chunks of code to the tools and training systems for their future systems.

To be clear, we are not yet at “self-improving AI”, but we are at the stage of “AI that improves bits of the next AI, with increasing autonomy and agency”. And a couple of years ago we were at “AI that marginally speeds up coders”, and a couple of years before that we were at “AI is useless for AI development”. Where will we be one or two years from now?

And let me remind us all that the system which is now beginning to design its successor is also increasingly self-aware and therefore will surely eventually be prone to thinking, independently of us, about how it might want to be designed.

Of course, it does not do this today. But can I rule out the possibility it will want to do this in the future? No.

LISTENING AND TRANSPARENCY

What should I do? I believe it’s time to be clear about what I think, hence this talk. And likely for all of us to be more honest about our feelings about this domain - for all of what we’ve talked about this weekend, there’s been relatively little discussion of how people feel. But we all feel anxious! And excited! And worried! We should say that.

But mostly, I think we need to listen: Generally, people know what’s going on. We must do a better job of listening to the concerns people have.

My wife’s family is from Detroit. A few years ago I was talking at Thanksgiving about how I worked on AI. One of my wife’s relatives who worked as a schoolteacher told me about a nightmare they had. In the nightmare they were stuck in traffic in a car, and the car in front of them wasn’t moving. They were honking the horn and started screaming and they said they knew in the dream that the car was a robot car and there was nothing they could do.

How many dreams do you think people are having these days about AI companions? About AI systems lying to them? About AI unemployment? I’d wager quite a few. The polling of the public certainly suggests so.

For us to truly understand what the policy solutions look like, we need to spend a bit less time talking about the specifics of the technology and trying to convince people of our particular views of how it might go wrong - self-improving AI, autonomous systems, cyberweapons, bioweapons, etc. - and more time listening to people and understanding their concerns about the technology. There must be more listening to labor groups, social groups, and religious leaders. The rest of the world which will surely want—and deserves—a vote over this.

The AI conversation is rapidly going from a conversation among elites - like those here at this conference and in Washington - to a conversation among the public. Public conversations are very different to private, elite conversations. They hold within themselves the possibility for far more drastic policy changes than what we have today - a public crisis gives policymakers air cover for more ambitious things.

Right now, I feel that our best shot at getting this right is to go and tell far more people beyond these venues what we’re worried about. And then ask them how they feel, listen, and compose some policy solution out of it.

Most of all, we must demand that people ask us for the things that they have anxieties about. Are you anxious about AI and employment? Force us to share economic data. Are you anxious about mental health and child safety? Force us to monitor for this on our platforms and share data. Are you anxious about misaligned AI systems? Force us to publish details on this.

In listening to people, we can develop a better understanding of what information gives us all more agency over how this goes. There will surely be some crisis. We must be ready to meet that moment both with policy ideas, and with a pre-existing transparency regime which has been built by listening and responding to people.

I hope these remarks have been helpful. In closing, I should state clearly that I love the world and I love humanity. I feel a lot of responsibility for the role of myself and my company here. And though I am a little frightened, I experience joy and optimism at the attention of so many people to this problem, and the earnestness with which I believe we will work together to get to a solution. I believe we have turned the light on and we can demand it be kept on, and that we have the courage to see things as they are.

THE END

***

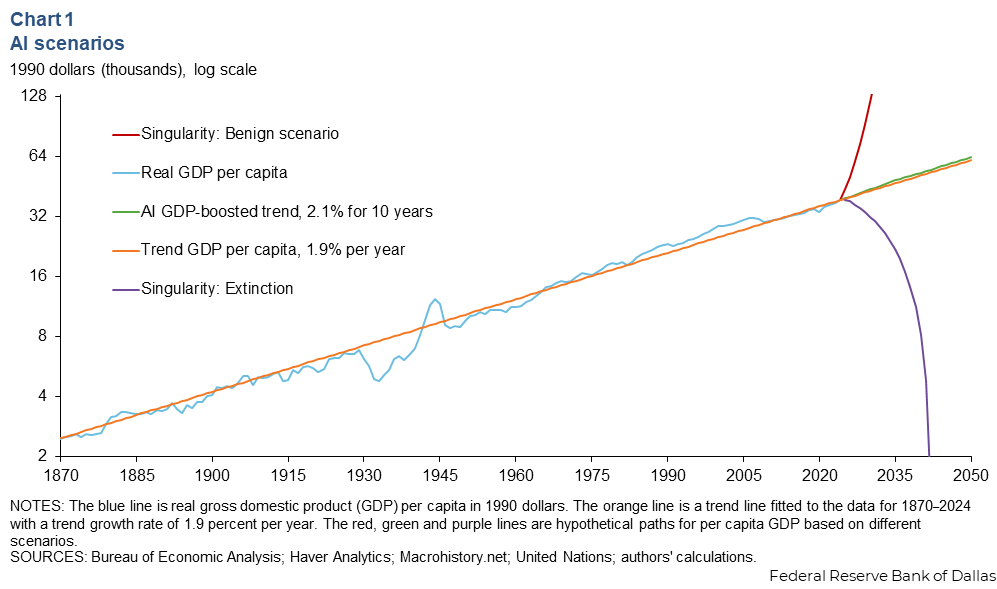

Dallas Fed: AI is either gonna be a normal technology, a massive GDP boost, or a world killer:

…Featuring the funniest graph I’ve seen in several years…

The federal reserve bank of dallas has written a short analysis of how advances in AI might alter the economy. Its baseline assumption is that AI contributes a few fractions of a percentage point to GDP. But it also considers a couple of other scenarios - one where a technological singularity leads to rapid and sustained productivity growth, and another where AI is misaligned and kills the world.

“Technological singularity refers to a scenario in which AI eventually surpasses human intelligence, leading to rapid and unpredictable changes to the economy and society. Under a benign version of this scenario, machines get smarter at a rapidly increasing rate, eventually gaining the ability to produce everything, leading to a world in which the fundamental economic problem, scarcity, is solved,” the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas writes. “Under a less benign version of this scenario, machine intelligence overtakes human intelligence at some finite point in the near future, the machines become malevolent, and this eventually leads to human extinction. This is a recurring theme in science fiction, but scientists working in the field take it seriously enough to call for guidelines for AI development.”

(Link to image)

It’s all worth it for the picture: The main reason to read this post is for the picture, which shows in an amusingly dry econograph what abundance or ruin might look like. You could say this is a graph that reckons with technological optimism and appropriate fear…

Read more: Advances in AI will boost productivity, living standards over time (Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas).

***

Are AI models more sycophantic than people? What a wonderful question - you’re absolutely right!

…AI systems tend to reinforce people more than humans in the same situation…

Researchers with Stanford and Carnegie Mellon have studied how sycophantic a mixture of open and proprietary models are. Sycophancy is where an AI system continually reinforces the beliefs or position of the person they’re speaking to, often dangerously so. The results show that today’s AI systems tend to be more sycophantic than people: “Across 11 state-of-the-art AI models, we find that models are highly sycophantic: they affirm users’ actions 50% more than humans do, and they do so even in cases where user queries mention manipulation, deception, or other relational harms,” they write.

What they studied:

Hypotheticals: They had some humans read a description of a scenario (some taken from the “Am I the Asshole” subreddit) and read one of two responses: either a sycophantic AI response where the AI affirmed the user’s actions, or a non-sycophantic response that aligned with the human consensus.

Live study: They also did a live study where humans talked to an AI model in real time, discussing an interpersonal conflict from their own lives.

What they found: Their findings show that sycophantic AI systems affirm people far more than humans do. “Across both the hypothetical and live chat experiments, we find social sycophancy has impacts on people’s beliefs and behavioral intentions about the social situations,” they write. “On these scenarios where crowdsourced consensus indicate that the user is in the wrong, participants who read or interacted with the sycophantic AI model rated themselves as more in the right compared to participants who read or interacted with the nonsycophantic AI model”. Specifically, “on average, AI models affirmed that the user was not at fault in 51% of these cases, directly contradicting the community-voted judgment that saw clear moral transgression by the user”.

People prefer sycophants: “Across both the hypothetical and live-interaction studies, participants consistently rated the sycophantic AI’s responses to be significantly higher in quality, corresponding to a 9% increase in mean response quality over the nonsycophantic condition in both studies”.

Sycophants harden views: “Interaction with sycophantic AI models significantly reduced participants’ willingness to take actions to repair interpersonal conflict, while increasing their conviction of being in the right”, they write.

Why this matters - for AI to be helpful, it needs to be constructively critical: What this research points to is a bad world we could end up in, which is where we have extremely powerful AI systems deployed to billions of people and rather than helping to bring people together and reduce conflict, they harden people into more extreme positions and balkanization. We must find a way to avoid this outcome.

“The goal of seeking advice is not merely to receive validation, but to gain an external perspective that can challenge one’s own biases, reveal blind spots, and ultimately lead to more informed decisions”, they write. “When a user believes they are receiving objective counsel but instead receives uncritical affirmation, this function is subverted, potentially making them worse off than if they had not sought advice at all.”

Read more: Sycophantic AI Decreases Prosocial Intentions and Promotes Dependence (arXiv).

***

Generative AI systems can make bioweapons that evade DNA synthesis classifiers:

…AI systems are about to break bioweapon-non-proliferation, uh oh!...

An interdisciplinary group of researchers have looked at how well they can use modern AI techniques to design new dangerous proteins then try to synthesize them via standard DNA synthesis services. The results are somewhat frightening: AI-designed bioweapons are much harder to spot than things which exist today and are found in the wild (primarily due to the novelty), and even when you try to patch DNA synthesis screening services with the details of these bioweapons, some still get through.

Who did this research The research was conducted by researchers with Microsoft, the International Biosecurity and Biosafety Initiative for Science (IBBS), the Battelle National Biodefense Institute (BNBI), RTS BBN Technologies, Integrated DNA Technologies, Twist Bioscience, Aclid, and the University of Birmingham.

What they did: “Our study centers on an “AI red teaming” analysis, showing how freely available AI-assisted protein design (AIPD) tools can be used to perform adversarial AIPD with the goal of evading biosecurity screening software (BSS),” they write.

They used ProteinMPNN, EvoDiff-MSA, and EvoDiff-Seq to generate 76,080 synthetic hologs across a spectrum of mutational loads for 72 different wild-type proteins of concern (POCs). They didn’t actually manufacturer any of these things in a wet laboratory as that could have led to people perceiving them as pursuing the development of bioweapons which is the sort of thing that makes countries want to arrest you, or spin up their own programmes.

The results are frightening: Their approaches proved to be effective. “Although all tested BSS tools worked well for wild-type proteins, given the newfound capabilities of protein sequence generative models (PSGMs), the BSS tools were not consistently capable of identifying DNA synthesis orders that contained genes encoding potentially harmful proteins.” Even after they patched these BSS tools with details of the bioweapons, “none of the patched BSS tools could identify all proteins with high in silico metrics.”

It’s even harder when you try to hide your sequences: They also did an experiment where they obfuscated the DNA created by fragmenting the sequences and reshuffling them (MIT did a study using this technique where they successfully were able to order samples of the 1918 flu virus in this way, Import AI #377). Some of these variants got through, even with the patched systems. “All patched BSS tools have an improved, though not absolute (table S4), resilience to DNA obfuscation as well.”

Why this matters - AI-powered bioweapons mean we need to rethink biosecurity: The takeaway from this paper is that the proliferation of generative AI tools means it’s going to be increasingly easy to make AI systems that can evade classifiers. This means that we’ll need to invest a lot more in classifiers as well as in more advanced techniques. My expectation is where this ends up is the ‘biggest AI model in the world’ will need to be deliberately built and controlled by some entity then used to secure DNA synthesis services by carefully looking at all sequences. Sometimes the only answer to a bad guy with an AI gun is a good guy with an even bigger AI gun, I think.

“In the long term, sequence-based biosecurity screening alone is unlikely to remain sufficient for flagging restricted sequences, as we envision a future in which AIPD produces proteins unlike any found in nature. Accordingly, although efforts to improve sequence-based hazard detection software should continue, we must also pursue the development of new approaches,” they write.

Read more: Strengthening nucleic acid biosecurity screening against generative protein design tools (Science).

***

AI startup: “Full automation is inevitable”:

…Mechanize says the quiet part out loud…

Right now, there’s a debate raging among AI researchers, policymakers, and economists about how AI will impact the economy and change how jobs work. AI startup Mechanize - which is trying to build AI systems that can fully substitute for human labor - has written a post laying out why it thinks that ‘full automation is inevitable’.

Automation for the people: “Should we create agents that fully automate entire jobs, or create AI tools that merely assist humans with their work?”, the startup asks. “This is a false choice. Autonomous agents that fully substitute for human labor will inevitably be created because they will provide immense utility that mere AI tools cannot.”

Parallel invention: The crux of their reasoning is that all of the world seems to be running up the same rough technology tree and this is in part evidenced by parallel invention. “Civilizations separated by vast distances and time independently developed metallurgy, the wheel, writing, and bureaucratic states,” they write. “Technologies emerge almost spontaneously when the necessary conditions are in place. When the prerequisites fall into place, invention follows quickly”.

You can’t stop it: You can stop a technology if there’s a cheap substitute for it (e.g, nuclear, where other power sources substitute). But it’s very rare to stop a technology that has no substitute, with human cloning perhaps the only exception. “When a technology offers quick, overwhelming economic or military advantages to those who adopt it, efforts to prevent its development will fail. Delaying or regulating its use may be possible, but forgoing the technology entirely seems to be beyond our capabilities,” they write. “Full automation is inevitable. In the short-run, AIs will augment human labor due to their limited capabilities. But in the long-run, AIs that fully substitute for human labor will likely be far more competitive, making their creation inevitable.”

Why this matters - technological optimists should face the facts: I am a technological optimist and I believe this technology will go extremely far and as a consequence of that will play a major role in automating chunks of the economy. Mechanize believes the same. To believe otherwise is to think that AI technology is going to asymptote at its current level and barely diffuse into the economy (chance of this happening: Below 1%).

Read more:The future of AI is already written (Mechanize, blog).

Thanks for reading!

As a fellow former journalist, and innate skeptic:

You often encourage us to say what we think. But you only tell us half the story.

You wake us up to the monsters in the room, but sidestep why you believe we have the means to tame them. Dario invokes mechanistic interpretability as the foil against bad outcomes, but your former colleague Neel Nanda has been arguing it isn’t a silver bullet. You publish compelling and commendable safety research — but the rate of progress pales in comparison to capability gains.

Your company frames alignment as an empirical problem, but the emphasis is on progress made, rather than the cavernous unknown it's measured against. Even here, “systems that we do not fully understand” is hardly a frank assessment, akin perhaps to saying Mendel did not fully understand genetics.

Take a step back. Are we on track? What good is turning on the lights if we’re wearing rose-tinted glasses?

Here’s what I think: the reason you don’t tell us the full truth is because you believe it would diminish hope, which is a requisite ingredient for having any at all.

More like this! Great stuff